THE MEMORIAL ARCHIPELAGO

WORK IN PROGRESS

INTRODUCTION

The Gulag system has left a void in the Russian consciousness, a “manufactured forgetting” where the physical remnants of the

system are dissolving into the landscape. In contemporary Russia, the state excels at consolidation, converting memory into sani-

tized symbols while the actual foundations of the camps are absorbed by the tundra. Where the state refuses to preserve, geogra-

phy remains—and geography always forgets.

This thesis contends that a singular memorial site is insufficient; if architecture relegates itself to one location, it risks state politici-

zation and sterilization. The scale of the system cannot be comprehended through one intervention. To even attempt to understand

its scale, the architecture must be distributed.

This investigation proposes a Memorial Archipelago: a decentralized, resilient network of interventions designed to resist state ap-

propriation and restore legibility to the erased void. Spanning four distinct conditions—Genesis (Solovetsky), Metastasis (Vorkuta),

Hardening (Butugychag), and Terminus (The Kolyma Highway)—this project constructs the memories that operate in the silence.

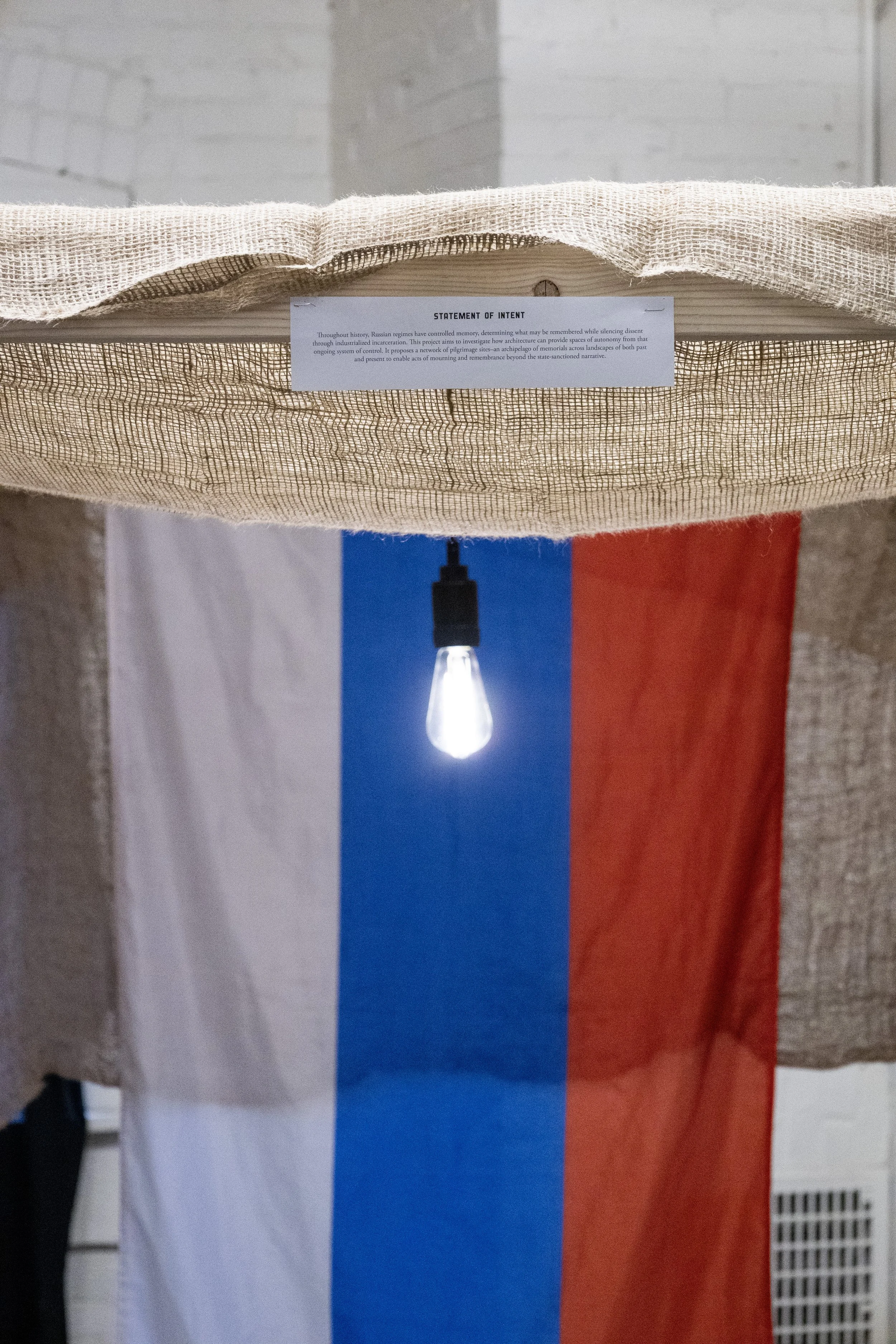

Throughout history, Russian regimes have controlled memory, determining what may be remembered while silencing dissent

through industrialized incarceration. This project aims to investigate how architecture can provide spaces of autonomy from that

ongoing system of control. It proposes a network of pilgrimage sites–a family of memorials across landscapes of both past and

present to enable acts of mourning and remembrance beyond the state-sanctioned narrative.

STATEMENT OF INTENT

PROBLEM, PROVOCATION, DETERMINATION

The Gulag endures because the state engineered its amnesia. Its violence erased, its trauma folded into daily life.

If the state has manufactured forgetting, what happens to this inhumanity when its buried rather than remebered?

Where the state compels neglect, landscape digests the savagery all the while architecture remains silently complicit. In searching

the landscapes of these absences, I move among what remains, traces of what once was forbidden to recall.

I move through ruins of deliberate forgetting, seeking to design an architecture capable of holding atrocity without erasure.

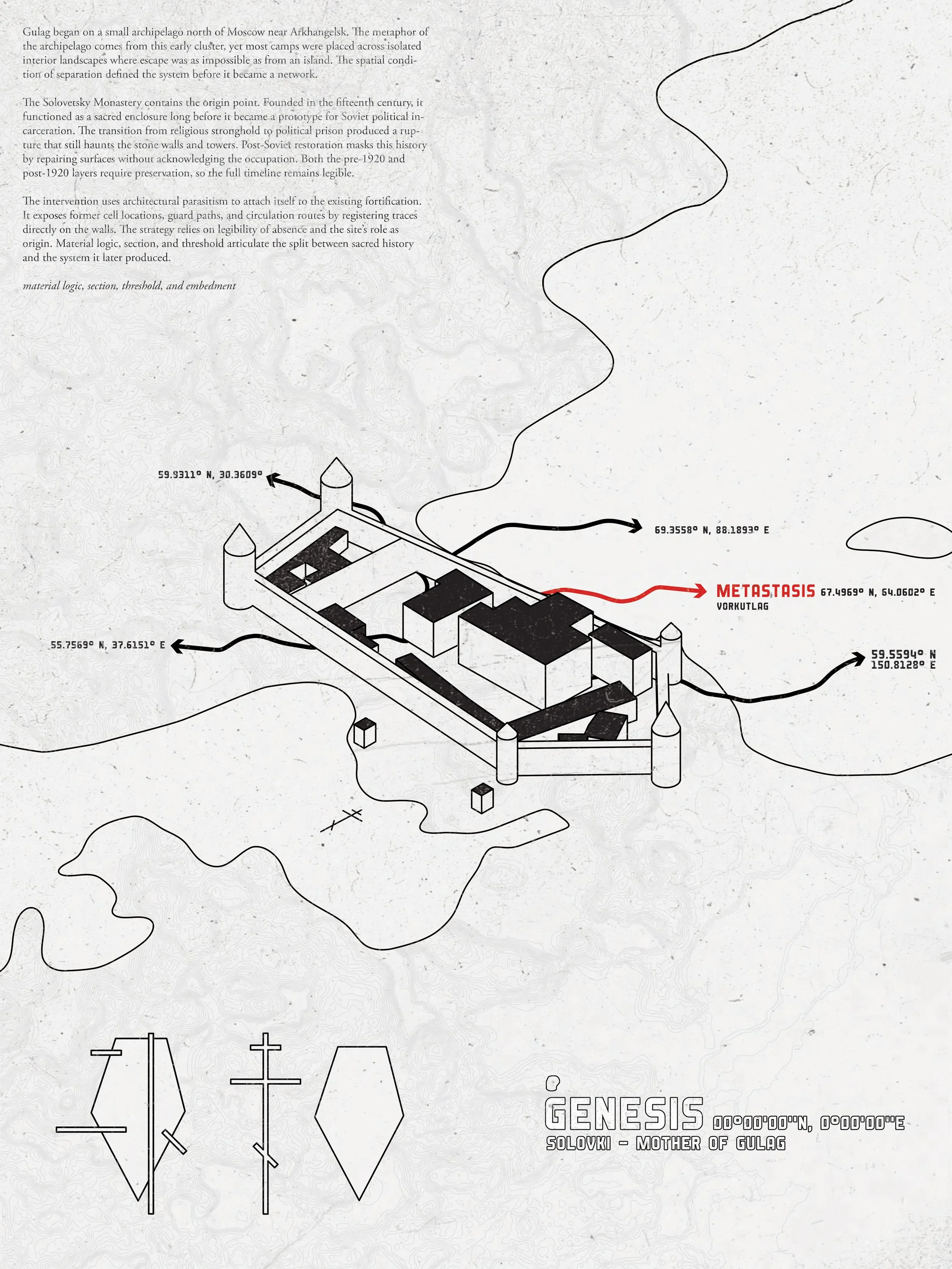

Gulag began on a small archipelago north of Moscow near Arkhangelsk. The metaphor of the archipel-

ago comes from this early cluster, yet most camps were placed across isolated interior landscapes where

escape was as impossible as from an island. The spatial condition of separation defined the system before

it became a network.

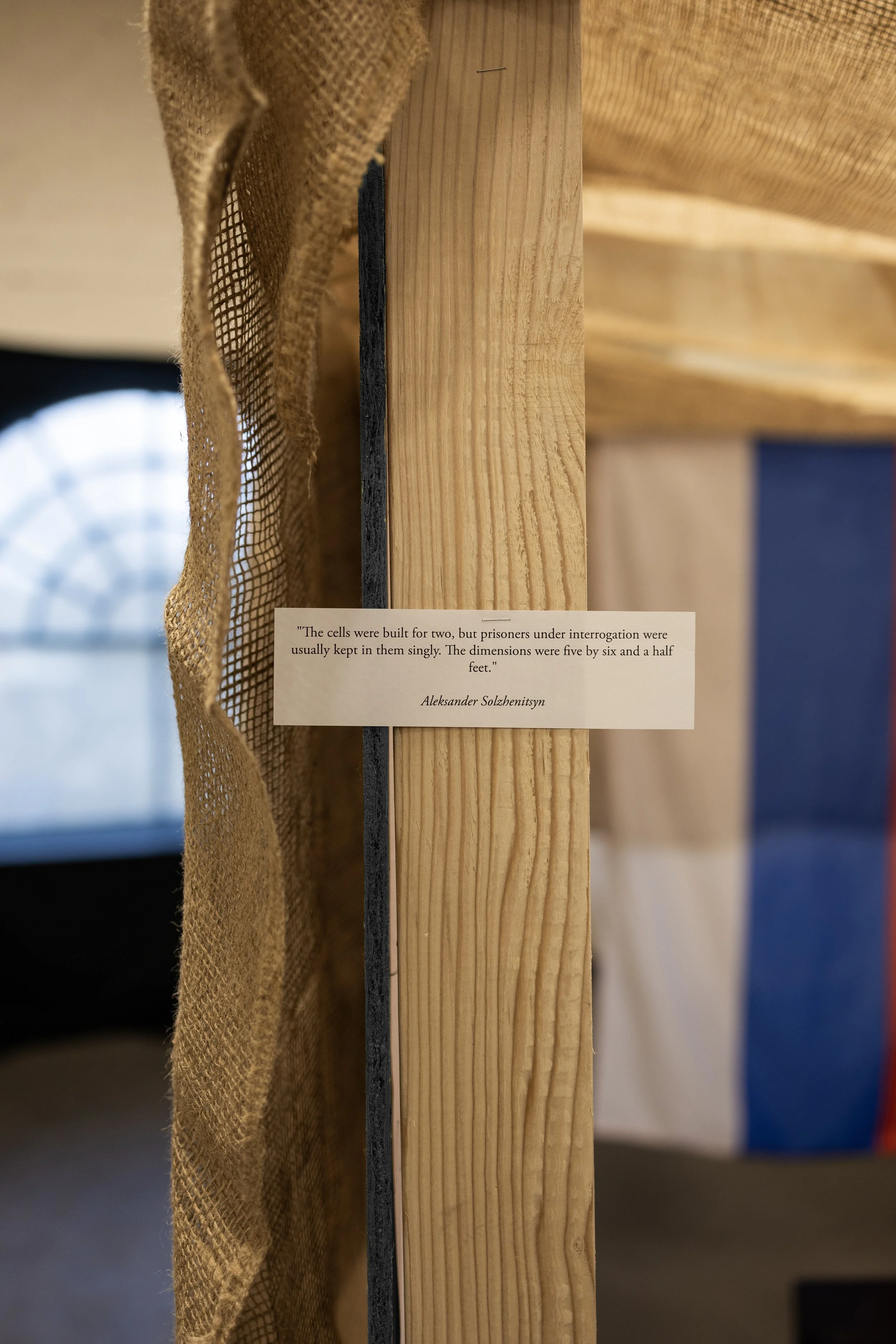

The Solovetsky Monastery contains the origin point. Founded in the fifteenth century, it functioned as a

sacred enclosure long before it became a prototype for Soviet political incarceration. The transition from

religious stronghold to political prison produced a rupture that still haunts the stone walls and towers.

Post‑Soviet restoration masks this history by repairing surfaces without acknowledging the occupation.

Both the pre‑1920 and post‑1920 layers require preservation, so the full timeline remains legible.

The intervention uses architectural parasitism to attach itself to the existing fortification. It exposes for-

mer cell locations, guard paths, and circulation routes by registering traces directly on the walls. The strate-

gy relies on legibility of absence and the site’s role as origin. Material logic, section, and threshold articulate

the split between sacred history and the system it later produced.

material logic, section, threshold, and embedment.

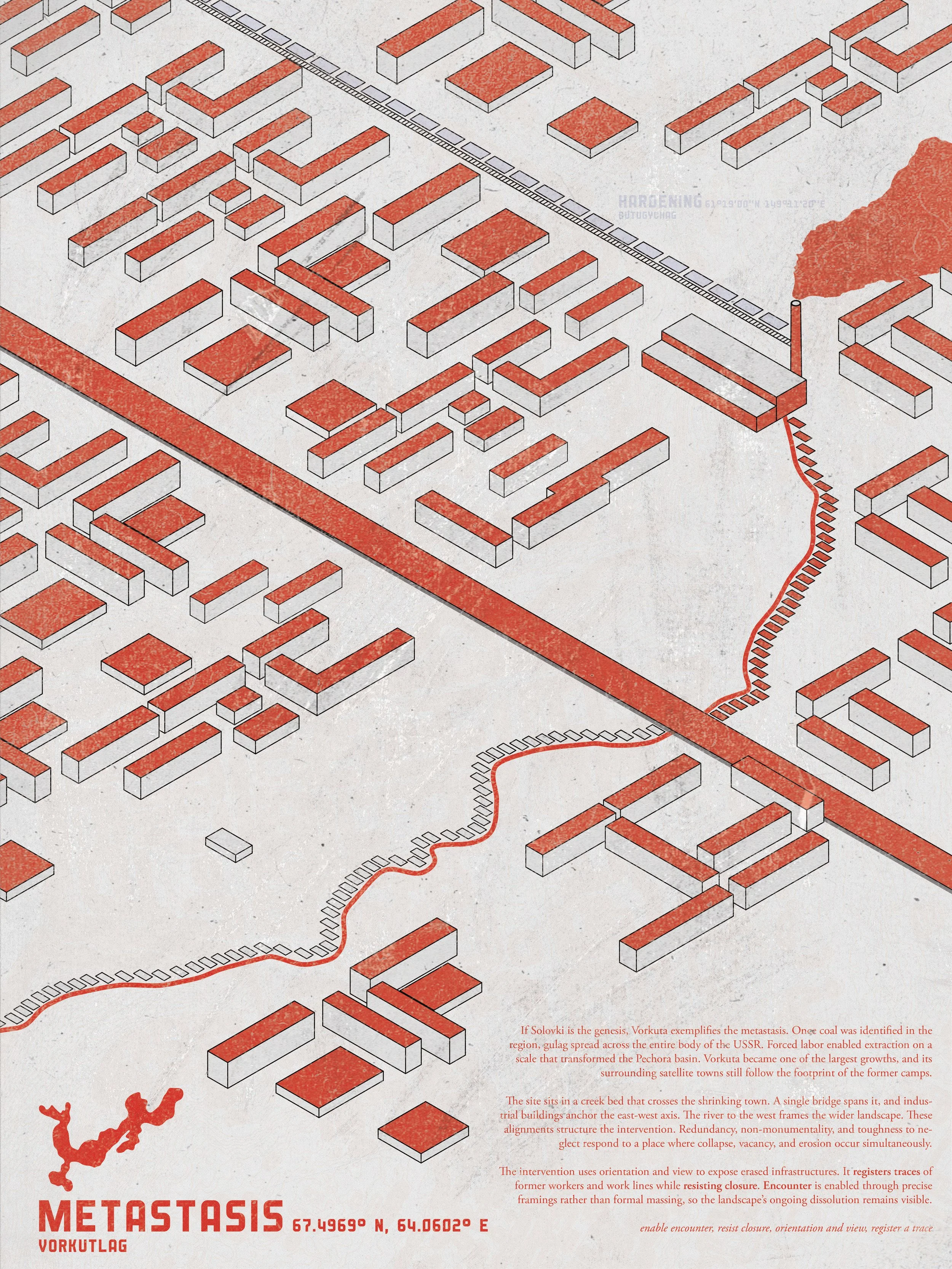

If Solovki is the origin, Vorkuta exemplifies the spread. Once coal was identified in the region, the NKVD

expanded the camp system into the Arctic. Forced labor enabled extraction on a scale that transformed

the Pechora basin. Vorkuta became one of the largest growths, and its surrounding satellites still follow the

footprint of former camps.

The site sits in a creek bed that crosses the shrinking town. A single bridge spans it, and industrial

buildings anchor the east‑west axis. The river to the west frames the wider landscape. These alignments

structure the intervention. Redundancy, non‑monumentality, and toughness to neglect respond to a place

where collapse, vacancy, and erosion occur simultaneously.

The intervention uses orientation and view to expose erased infrastructures. It registers traces of former

barracks and work lines while resisting closure. Encounter is enabled through precise framings rather than

formal massing, so the landscape’s ongoing dissolution remains visible.

enable encounter, resist closure, orientation and view, register a trace

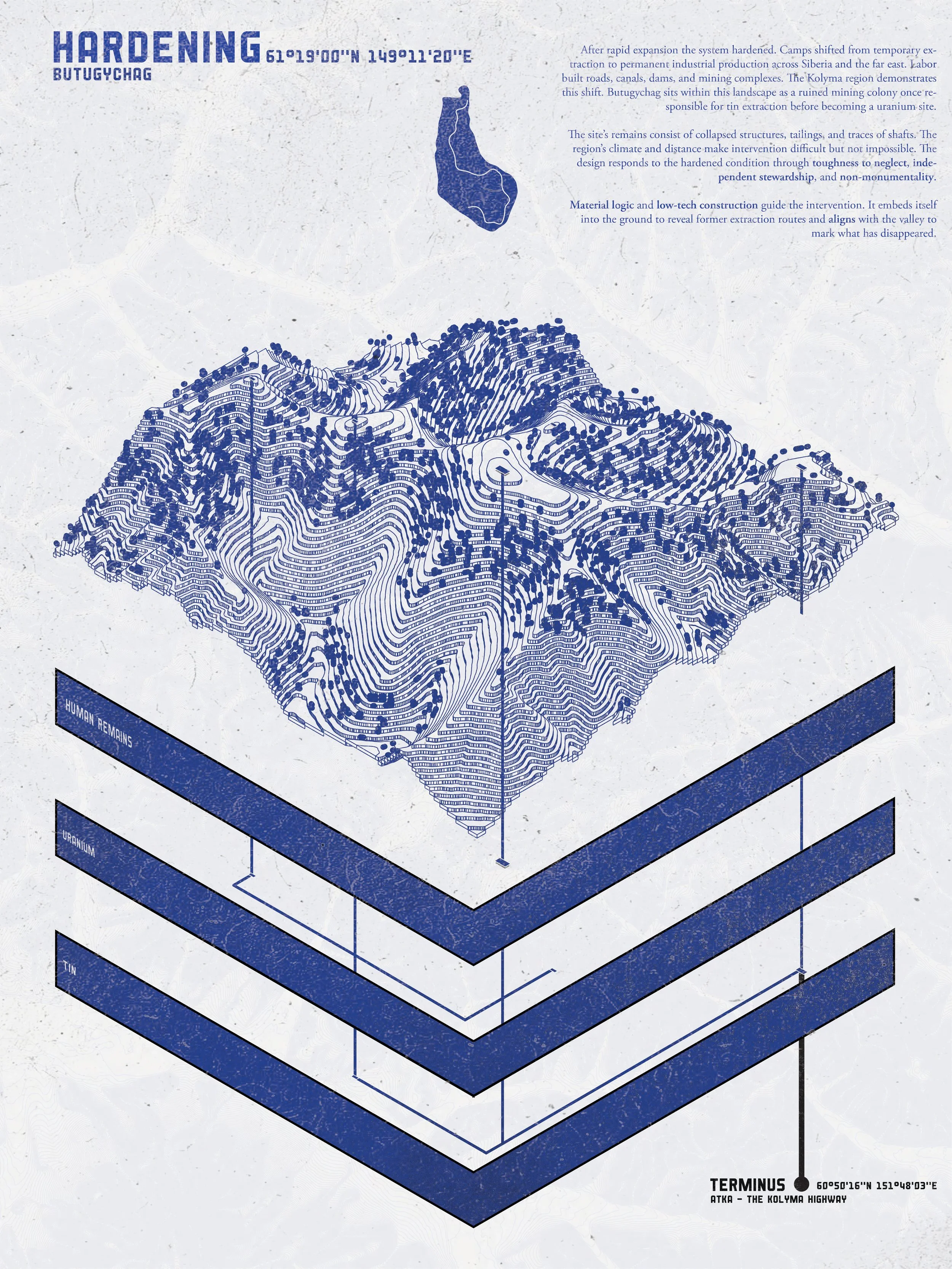

After rapid expansion the system hardened. Camps shifted from temporary extraction to permanent

industrial production across Siberia and the far east. Labor built roads, canals, dams, and mining complex-

es. The Kolyma region demonstrates this shift. Butugychag sits within this landscape as a ruined mining

colony once responsible for tin extraction before becoming a uranium site.

The site’s remains consist of collapsed structures, tailings, and traces of shafts. The region’s climate and

distance make intervention difficult but not impossible. The design responds to the hardened condition

through toughness to neglect, independent stewardship, and non‑monumentality.

Material logic and low‑tech construction guide the intervention. It embeds itself into the ground to reveal

former extraction routes and aligns with the valley to mark what has disappeared. Section establishes a

precise threshold between ordinary terrain and charged ground.

material logic, low-tech, scalability, orientation

The project concludes along the Kolyma Highway where many prisoners reached their terminus. Their

transit ranged from rail to ship to walking, ending in the far‑east extraction zones. Mortality was so high that

the road itself contains the remains of those who built it. Infrastructure and burial occupy the same line.

Near Atka the highway passes through a region still tied to extraction but nearly abandoned. The ab-

sence of recognition along this route produces a void where the scale of the system is no longer legible.

The site’s sparsity and distance define the intervention

The design bases itself on legibility of absence, resistance to consolidation, and toughness to neglect.

It embeds markers along the roadside that register traces of camp routes and burial grounds without

monumentalizing them. Orientation follows the highway, so the viewer confronts the linear history of forced

movement. The intervention enables witnessing by exposing the void rather than filling it.

embedment, resist closure, material logic, enable witnessing